Bebop: Jazz’s Game-Changer

The Big Bang of Bebop

When jazz pivoted on its heel and spun into the bebop era, it wasn’t just a change—it was a metamorphosis. This was not merely evolution; it was a revolution in riffs. The bebop era, a term that still causes the hearts of jazz enthusiasts to skip a beat, marked a seismic shift in the landscape of music during the early 1940s. If one were to define bebop, it would be like trying to capture the essence of a whirlwind—dynamic, forceful, and impossible to ignore.

The Big Bang of bebop didn’t have a singular moment of inception but was more of an accumulation of musical curiosity among the jazz maestros of the time. It was born out of late-night jam sessions where the currency was creativity and the stakes were always high. These sessions were the alchemic playgrounds where traditional jazz harmonies and structures were dismantled and reassembled into something daringly complex and utterly fresh.

The bebop era was characterized by its fast tempos, intricate melodies, and a propensity for improvisation that stretched the bounds of what was musically possible. It was an era that took the swing notes of its predecessors and sliced them into unexpected rhythms, a soundscape where the predictability of the dance floor gave way to the virtuosity of the musicians’ solos. In bebop, you find the birth of “the blow,” where soloists would engage in a musical discourse, each trying to outdo the other with their fluency and inventiveness.

These pioneering musicians became the architects of a new jazz language, one with a lexicon that was rich with syncopation and chromaticism. The phrase ‘playing outside’ took on new life, as bebop musicians would often play notes outside the conventional chord progressions, creating tension and release that both disoriented and delighted the listener.

The Big Bang of bebop wasn’t silent; it was loud and resolute. It echoed through the smoky clubs of Harlem, bounced off the walls of the Savoy, and resonated in the hallowed halls of Minton’s Playhouse. This was where bebop found its voice, and from there, it spoke to the world—a world that was, perhaps, not quite ready for its audacious new dialect.

But ready or not, bebop had arrived, and it would leave an indelible mark on the fabric of music, forever changing what was possible within the span of a few bars. This was the era that broke the rules so thoroughly that it wrote new ones, only to break those too, in the pursuit of pure, unadulterated expression.

The Architects of Bebop

The Architects of Bebop were not just musicians; they were sonic explorers, rebels with a cause, and creators of a movement that would etch a permanent groove in the records of music history.

Dizzy Gillespie: Trumpeting New Heights

Dizzy Gillespie stood at the vanguard, his cheeks ballooning with each forceful blow into the trumpet, conjuring notes that seemed to defy gravity. With a beret perched atop his head and glasses framing his eyes, Dizzy wasn’t just playing music; he was painting with sound, vibrant strokes on the canvas of silence. His contributions to bebop are etched in the halls of music history, with compositions like “A Night in Tunisia” that blend complex rhythms with a melodic fluidity that had never been heard before. Dizzy’s audacious approach to music twisted the traditional into the extraordinary, inviting listeners into an exhilarating auditory adventure.

Charlie Parker: Saxophone Savant

Then there was Charlie Parker, the Saxophone Savant, whose fingers danced across the keys with a ferocity and precision that left onlookers mesmerized. Bird, as he was affectionately known, was not one to play it safe. He soared over the scales, each note a defiant leap, each run a bold flight path that charted new territories in the realm of jazz. In pieces like “Ko-Ko,” Parker’s alto saxophone didn’t just sing; it spoke a language of rhythm and rebellion, teaching the world new definitions of harmony and musical possibility.

Thelonious Monk: Piano Prodigy

In the realm of the ivories, Thelonious Monk emerged as the Piano Prodigy, a maestro of dissonance that made the off-kilter sound on point. His compositions were audacious puzzles, where each piece fit in a way that only Monk could envision. With classics like “Round Midnight,” Monk did not just play notes; he played the spaces between them, creating a tapestry of sound that was as intriguing as it was innovative.

Bud Powell: Virtuosity Unleashed

The narrative of bebop would be incomplete without the mention of Bud Powell, whose prowess on the piano earned him the title of Virtuosity Unleashed. Bud’s style was a frenetic whirlwind, his fingers a blur, each keystroke a thunderbolt that commanded attention. In “Tempus Fugit” and beyond, Powell’s approach to the piano was a radical departure from the norm, a testament to the power of bebop to break barriers and build new ones out of the rubble.

Max Roach: Drumming to a Different Beat

In the percussive tapestry of bebop, Max Roach was the heartbeat, his sticks striking skins and cymbals to drum a rhythm that would pulse through the genre’s very core. Roach was no ordinary timekeeper; he was a rhythmic alchemist, transforming the role of the drum set in jazz from mere background to a leading voice in the ensemble. His approach was both a percussive onslaught and a delicate whisper, a duality that echoed the complexity of bebop itself.

With a virtuosic command of syncopation and an innovative use of the drum kit, Roach crafted beats that were as imaginative as they were impactful. In compositions like “The Drum Also Waltzes,” Max Roach didn’t just play music—he told stories, his rhythms narrating tales of tension, triumph, and transcendence. His drum solos were marvels of musical architecture, erecting structures of sound that stood tall and unmatched.

Max Roach’s contribution to bebop went beyond mere technique; he imbued the music with a sense of urgency and a call to freedom, embodying the spirit of the movement. He drummed not just to a different beat, but to a new rhythm of possibilities, inspiring generations of musicians to see the drum set as a canvas of endless potential.

Bebop’s Musical Mosaic

Within the intricate tapestry that is bebop lies a complexity that can be dissected but never diminished. Each bebop tune is an ecosystem of sound, its anatomy a complex interplay of elements that demands the listener’s full engagement.

The Anatomy of a Bebop Tune begins with its head – the main theme, typically a winding, convoluted melody that sets the stage for what’s to come. It’s here that the tune’s character is established, a musical thesis that will be debated and discussed through each musician’s interpretation. The solos that follow act as the body, the flesh and blood where each artist injects their own essence into the composition. Here, the language of bebop is spoken in its purest form – notes and phrases darting and diving like swifts at dusk, each a masterclass in musical expression.

Melody Meets Madness in Bebop’s Harmonic Structure. Chords are stacked and stretched, leading to a harmonic labyrinth that is as unpredictable as it is captivating. The progression of these chords is not just a path, but a series of stepping stones across a rhythmic river, each one placed with purpose and intent. It’s a harmonic high-wire act, with each musician balancing deftly, never falling into the mundane.

The Rhythmic Rebellion of Bebop is where the true insurgence lies. Time is treated not as a metronome’s slave, but rather a flexible concept, to be pushed and pulled at the musician’s whim. Syncopation becomes the norm, the strong beats often abandoned for the weak, creating a sense of anticipation and surprise that keeps the audience on the edge of their seats.

Improvisation is the Bebop Musician’s Canvas. Here, the rules of harmony and theory are known but often ignored, as the artist paints with audacious strokes of spontaneous creation. It’s a thrilling high-wire act without a net, as musicians navigate through the chord changes, sometimes flirting with chaos, always returning to order. The solos are conversations, debates, passionate arguments that take place within the framework of the tune, each artist’s voice distinct, clear, and potent.

In the realm of bebop, these components merge to form a mosaic of musical genius – a genre that is as challenging to play as it is rewarding to hear. Each performance is a unique creation, never to be replicated, always to be revered.

Bebop’s Cultural Cacophony

Bebop’s Cultural Cacophony resonated far beyond the boundaries of music, infiltrating the very sinews of cultural expression of its time.

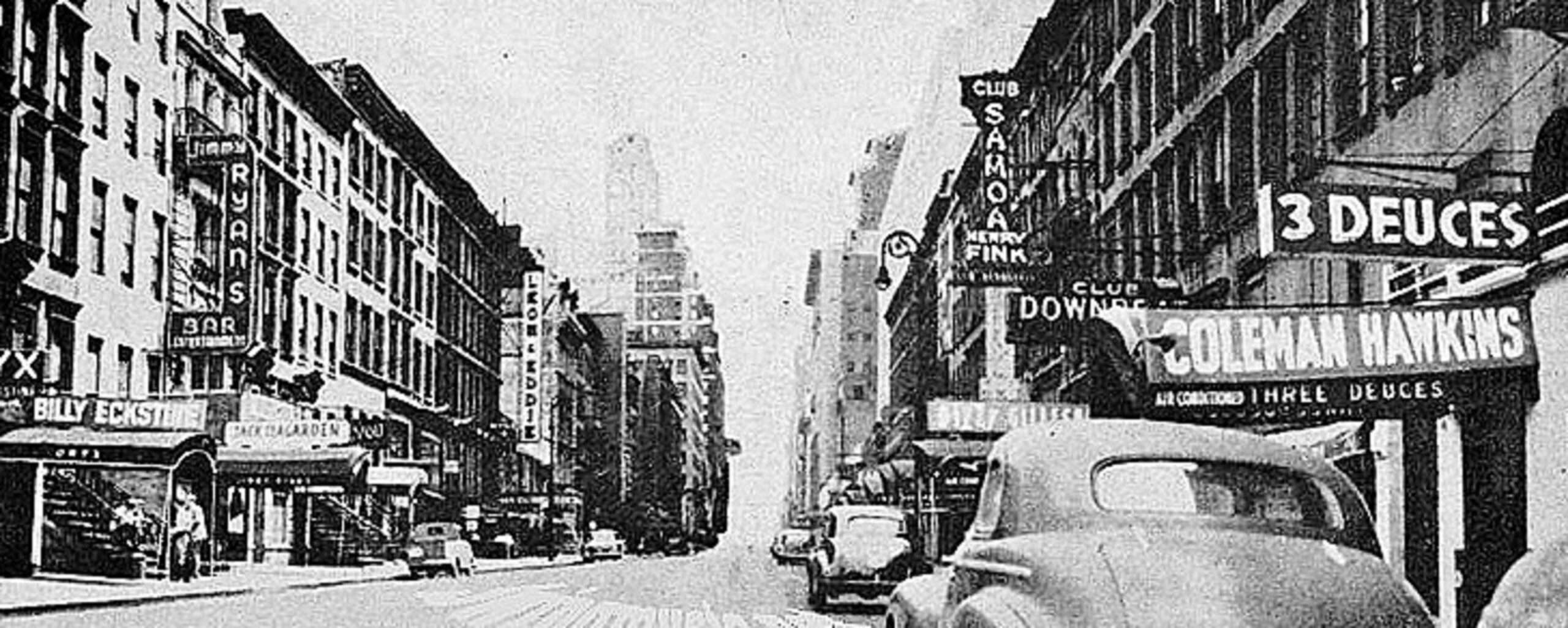

Jazz Joints: The Nightclubs of the Bebop Movement were not just venues; they were crucibles of creation where the music’s heat was ever-present. Places like Minton’s Playhouse and the Three Deuces on 52nd Street became hallowed ground for bebop aficionados. Within these dimly lit sanctuaries, the clink of glasses and the murmur of conversation served as the prelude to the night’s sonic odyssey. These clubs were the throbbing heart of the movement, pulsing with the beats of Gillespie, Parker, and Monk, their walls steeped in the sweat and smoke of musical revolution.

Fashion and Slang: The Style of Bebop were the sartorial and linguistic reflections of its rebellious heart. Zoot suits with wide lapels and pegged trousers were more than attire; they were statements of nonconformity, the outward manifestations of an inward revolution. The language too, was infused with the spirit of bebop—words like ‘cool’, ‘dig’, and ‘hip’ embedding themselves into the lexicon, each term a verbal nod to the subculture that bebop had spawned. It was a lexicon that was as rhythmic and improvisational as the music itself, a style that spoke of a desire to be different, to be heard, to be seen on one’s own terms.

Bebop’s Influence on the Beat Generation cannot be overstated. It provided the soundtrack to a literary movement that would challenge the status quo with the same fervor as the musicians challenged musical boundaries. The bebop aesthetic, with its emphasis on spontaneity, authenticity, and an unyielding disdain for the conventional, found kindred spirits in writers like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. Their stream-of-consciousness prose mirrored bebop’s improvisational nature, both seeking a purity of expression that was raw and unfiltered. The restless energy of bebop found its echo in the pages of ‘On the Road’ and ‘Howl’, encapsulating a sense of disillusionment and yearning that defined a generation.

Through these venues, styles, and philosophies, bebop did more than just contribute a chapter to the annals of music history—it penned a cultural manifesto that would reverberate through the decades, its riffs and revolutions continuing to inspire long after the final note was played.

The Sound of Revolution: Bebop’s Influence on Modern Jazz

The Sound of Revolution that bebop heralded was more than a mere riff in jazz; it was a clarion call that resonated into the future of the genre, influencing its many subsequent forms.

From Bebop to Hard Bop: A Smooth Transition, the lineage was clear. Hard bop took the bebop blueprint and added even more soul, a dash of blues, and a sprinkle of gospel. The transition was like a river flowing from its source, gathering new elements as it moved. Art Blakey and Horace Silver were among the craftsmen who carved this path, their music infusing bebop’s complex improvisations with a deeper, more resonant groove. Hard bop became the sound of the 1950s, a soundtrack for a generation seeking both sophistication and swing.

Cool Jazz: The Counterpart of Bebop emerged almost as a whispered answer to bebop’s exuberant shout. Where bebop was frenetic, cool jazz was subdued; where bebop was dense, cool jazz was spacious. It was the west coast’s retort to the east coast’s bebop frenzy. Musicians like Chet Baker and Dave Brubeck stood at the helm of this movement, their melodies lingering like a gentle fog over the Pacific, offering a smoother, more reflective take on the bebop spirit.

Fusion and Beyond: Bebop’s Legacy is undeniable in the threads of jazz’s rich tapestry. Fusion, the blending of jazz harmony with rock’s energy and funk’s rhythm, would not have been possible without the trail blazed by bebop. It set the precedent for experimentation, pushing the envelope of what jazz could be. In the electrified explorations of Miles Davis and the genre-bending escapades of Herbie Hancock, the spirit of bebop lives on, its essence distilled into new forms that continue to challenge and captivate.

Bebop’s influence permeates the very core of modern jazz, its echoes heard in the syncopated beats of hip-hop, the complex harmonies of neo-soul, and the improvisational spirit of contemporary jazz ensembles. It was, and continues to be, a revolution that refuses to be confined to a single era—a symphony of innovation that keeps on playing.

Understanding Bebop: The Listener’s Guide

The Listener’s Guide carves out a roadmap for the uninitiated and deepens the appreciation for the seasoned ear.

How to Listen to Bebop: An Appreciator’s Tips:

Begin with an open mind, expect the unexpected. Focus on the interaction between musicians—the push and pull, the conversation without words. Notice the nuances; the way a soloist might venture far from the melody, only to return just when you think they’re lost. Feel the rhythm, how it shifts and sways, and allow yourself to be carried by its current. Listen not just with your ears but with your soul. Bebop isn’t just heard; it’s felt.

The key to appreciating bebop lies in embracing its spontaneity and acknowledging its depth. Each listen reveals something new—a note, a beat, a feeling. This is the fabric of bebop: woven with innovation, patterned with genius, and meant to be unraveled one listen at a time.

Key Recordings That Define Bebop are essential listening for any jazz enthusiast. These recordings are not just songs; they are the chapters of bebop’s grand narrative, each track a story unto itself.

To truly grasp bebop’s spectacular innovations, one must engage with its music actively and attentively.

Here is a curated list of bebop tunes that epitomize the genre’s finest qualities, along with insights into their significance and what to listen for:

- “Ko-Ko” – Charlie Parker

- Innovation: Intricate improvisation over a harmonic structure.

- Listen for: Parker’s rapid-fire alto sax lines, complex harmonies, and the way his improvisations, while virtuosic, are always melodically grounded.

- “A Night in Tunisia” – Dizzy Gillespie

- Innovation: Fusion of Afro-Cuban rhythms with bebop harmony.

- Listen for: The song’s signature rhythmic figure and how Gillespie’s trumpet work weaves in and out of the Afro-Cuban groove with seamless agility.

- “Round Midnight” – Thelonious Monk

- Innovation: Use of dissonance and unconventional melodic structure.

- Listen for: Monk’s sparse yet impactful piano playing, characterized by its use of silence and surprising note choices that add tension and resolve unexpectedly.

- “Salt Peanuts” – Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker

- Innovation: Call-and-response interplay between the horns and rhythm section.

- Listen for: The playful, repetitive vocal phrase “Salt Peanuts” and the intricate exchanges between Gillespie’s trumpet and Parker’s sax.

- “Boplicity” – Miles Davis

- Innovation: Early example of the cool jazz sound that would follow bebop.

- Listen for: The smoother, more restrained approach to improvisation, and the contrapuntal interplay between the instruments.

- “Tempus Fugit” – Bud Powell

- Innovation: Advanced bebop piano techniques.

- Listen for: Powell’s lightning-fast right-hand lines, his left-hand comping, and the complex, fast-moving chord changes.

- “Shaw ‘Nuff” – Dizzy Gillespie

- Innovation: Blending of swing and bebop elements.

- Listen for: The song’s breakneck tempo and Gillespie’s use of syncopation and offbeat accents.

- “Conception” – George Shearing

- Innovation: Intricate block-chord piano style within a bebop context.

- Listen for: Shearing’s layered harmonies and the precision of his block-chord technique.

- “Straight, No Chaser” – Thelonious Monk

- Innovation: Unusual song form and melody.

- Listen for: The unique, angular melodic lines and Monk’s unconventional rhythmic placement.

- “Un Poco Loco” – Bud Powell

- Innovation: Latin-inspired rhythms melded with bebop complexity.

- Listen for: The interplay between the Afro-Cuban rhythm section and Powell’s virtuosic bebop piano lines.

- “Ornithology” – Charlie Parker

- Essential for its clever reworking of the chord changes from the standard “How High the Moon,” exemplifying the bebop practice of writing new, complex melodies over familiar progressions.

- “Bouncing with Bud” – Bud Powell

- Highlights Bud Powell’s innovative bebop piano style, characterized by his intricate right-hand lines and advanced harmonic concepts.

- “Groovin’ High” – Dizzy Gillespie

- A prime example of Gillespie’s virtuosity and innovative approach to trumpet playing, this tune also features a melody based on the chord changes of the standard “Whispering.”

- “Four Brothers” – Woody Herman

- Although not a small-group bebop recording, this Herman hit showcases the influence of bebop harmony and phrasing in big band settings, featuring a saxophone section that included three tenor and one baritone sax, a novel concept at the time.

- “Manteca” – Dizzy Gillespie

- This track is critical for understanding the fusion of bebop with Afro-Cuban rhythms, a new direction in jazz that Gillespie was instrumental in developing.

- “Scrapple from the Apple” – Charlie Parker

- This composition combines a complex bebop head with the chord changes of traditional jazz standards like “Honeysuckle Rose” and “I Got Rhythm,” showcasing the bridging of old and new in bebop.

- “Hot House” – Tadd Dameron

- Composed by one of bebop’s key architects, this piece features intricate melodies and chord progressions that became hallmarks of the genre.

- “Anthropology” – Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie

- Another Parker-Gillespie collaboration that has become a bebop standard, this tune is based on the chord changes to “I Got Rhythm,” a popular vehicle for bebop improvisation.

- “Dizzy Atmosphere” – Dizzy Gillespie

- Illustrates Gillespie’s ability to push the boundaries of trumpet technique and harmony, with a fast-paced tune that became a test piece for many jazz musicians.

- “52nd Street Theme” – Thelonious Monk

- Often played during jam sessions at famous bebop venues on New York’s 52nd Street, this tune became an anthem of the bebop movement.

The Language of Bebop

A Glossary is vital to understanding the genre’s unique vernacular.

“Chops” – Refers to a musician’s technical ability, particularly the proficiency and agility in playing their instrument.

“Woodshedding” – The act of practicing intensely and in seclusion to perfect one’s skills. The term implies a dedication to craft that is almost ascetic in nature.

“Licks” – These are pre-composed or previously improvised phrases of notes that musicians incorporate into their solos.

“Trading Fours” – A common practice in Bebop where musicians alternate solos every four bars, often seen in drum solos within a larger piece.

“Heads” – The main theme or melody of a tune, especially in the context of a jazz piece.

“Riff” – A repeated phrase used in solos and as accompaniment, a riff is usually melodically and rhythmically simple and catchy.

“Comp” (Comping) – Short for “accompanying,” it refers to the chords, rhythms, and countermelodies that an instrumentalist (usually a pianist or guitarist) creates to support a soloist.

“Blowing” – A term used to describe playing a solo, often used in the context of horn players.

“Changes” – Chord progressions in a tune. Bebop is known for its complex and rapid chord changes.

“The Bridge” – The B section of a typical 32-bar AABA song form. It’s a contrasting section that provides a departure from the main theme.

“Double Time” – A technique where the musician plays notes twice as fast as the underlying tempo, creating a sense of acceleration.

“Flat Five” (♭5) – A reference to the diminished fifth, an interval often used in Bebop to create tension.

“Dig” – To understand or appreciate. In a jazz context, it can mean to appreciate a musician’s style or a particular solo.

“Hip” – Something that’s very cool or in the know, particularly within the jazz community.

“Out” – Playing outside refers to improvising using notes that are not within the established key or chord structure, creating a dissonant sound.

“Cats” – A term referring to jazz musicians.

“Cutting Session” – A competitive jam session where musicians would try to outdo each other with their skills.

“Kicks” – Syncopated accents provided by the drummer or other members of the rhythm section.

“Up” or “Uptempo” – Describes a song with a fast pace. Bebop often features uptempo tunes that challenge the virtuosity of the musicians.

These terms paint a vivid picture of the bebop scene, where skill, style, and spontaneity were the currency of cool. Understanding this jargon is essential for anyone looking to delve deeper into the world of Bebop and jazz music in general.

The Technicality of Bebop

The Technicality of Bebop is not just in its execution, but in its very blueprint. It is here where we unlock the mechanics of a genre that revolutionized jazz.

Bebop Scales: A Breakdown unveils the scales that are the building blocks of bebop’s intricate solos and melodies. Take the Bebop Dominant Scale, for instance; it’s your regular Mixolydian mode with an added chromatic passing tone. This isn’t just a scale; it’s a tightrope, where each step is a note that must be placed with precision and purpose. These scales, with their syncopated rhythms and unexpected notes, are the DNA of bebop, giving it a sound that’s as distinct as a fingerprint.

The Bebop Dominant scale is essentially a Mixolydian scale with an added chromatic passing tone. The formula for a Bebop Dominant scale is as follows:

1 – Major 1st (Root)

2 – Major 2nd

3 – Major 3rd

4 – Perfect 4th

5 – Perfect 5th

6 – Major 6th

♭7 – Minor 7th (also known as the dominant 7th)

7 – Major 7th

8 – Octave

This scale is typically used over dominant 7th chords in jazz music. The addition of the major 7th (7) as a passing tone allows the scale to maintain a constant eight-note pattern, facilitating the alignment of chord tones with strong beats in the music. This characteristic makes it highly favored for use in Bebop improvisation.

Bebop Major Scale (often used over major 6th chords):

1 – Root

2 – Major 2nd

3 – Major 3rd

4 – Perfect 4th

5 – Perfect 5th

6 – Major 6th

♭7 – Minor 7th

7 – Major 7th

8 – Octave

Bebop Minor Scale (a variation of the Dorian mode with an added natural 7th):

1 – Root

2 – Major 2nd

♭3 – Minor 3rd

4 – Perfect 4th

5 – Perfect 5th

6 – Major 6th

♭7 – Minor 7th

7 – Major 7th

8 – Octave

Bebop Dorian Scale (similar to the Bebop Minor but with a different application):

1 – Root

2 – Major 2nd

♭3 – Minor 3rd

4 – Perfect 4th

5 – Perfect 5th

6 – Major 6th

♭7 – Minor 7th

♮7 – Major 7th (added chromatic passing tone)

8 – Octave

Bebop Half-Diminished Scale (a Locrian scale with an added natural 2nd):

1 – Root

2 – Major 2nd

♭3 – Minor 3rd

4 – Perfect 4th

♭5 – Diminished 5th

♭6 – Minor 6th

♭7 – Minor 7th

7 – Major 7th

8 – Octave

Complex Chords: The Backbone of Bebop Harmony form the sturdy framework upon which bebop’s daring improvisations are built.

In Bebop, chords are not mere triads; they are stacked with extensions and alterations that challenge both the player and the listener.

Extended chords, like the dominant seventh with a sharp eleventh, are not just thrown in for complexity’s sake—they’re there to add color, to provoke a feeling, to challenge the soloist and delight the listener. These chords are the pillars of bebop, supporting the weight of its innovative spirit.

Take, for instance, the iconic Bebop staple, the extended dominant chord. Not content with a simple dominant seventh, Bebop musicians often added ninths, sharp elevenths, and thirteenth intervals to their chords. These are chords rich with tension and color, demanding resolution but not in haste, savoring the dissonance they create. A Bebop dominant chord might look like this: G7#11, which translates to the notes G, B, D, F, A, C#, and E, each adding a layer to the harmonic fabric.

Moreover, Bebop musicians frequently utilized substitutions such as tritone or minor third substitutions to introduce further harmonic complexity and variety into their progressions. A tritone substitution involves replacing a dominant chord with another dominant chord a tritone (three whole steps) away. This creates a surprising shift in harmony that, while startling, resolves beautifully into the following chord, giving Bebop its signature unpredictability.

Additionally, the use of diminished chords as passing chords is a hallmark of the Bebop sound. These chords serve as a harmonic bridge between more stable chords, propelling the progression forward with a sense of motion and intrigue.

The intricate chordal structures in Bebop also allowed for more elaborate improvisational lines. Soloists could weave in and out of these complex harmonies with chromatic approaches, enclosures, and non-diatonic runs that would be at odds with more simplistic chord structures.

These harmonies are not just heard; they are felt. They pull at the listener, creating an ebb and flow of tension and release that is as unpredictable as it is satisfying. The complex chords of Bebop are not random; they are meticulously crafted, with each addition serving a purpose in the grand design of the composition. They invite the listener into a world of harmonic richness that is the very essence of Bebop’s enduring appeal.

The Soloing Strategy of Bebop Musicians is a high-stakes game of musical chess. Each soloist plays with a strategy, thinking several moves ahead. They take the themes, the chords, the scales, and weave them into solos that are both a homage to the tune and a declaration of individuality. A bebop solo is a balancing act, where spontaneity meets mastery, and the musician’s instrument becomes a conduit for their voice, their story, their soul.

In bebop, the technical is inextricable from the emotional. Each note, each chord, each scale is a step in a dance, a word in a poem, a color on a canvas. To understand bebop is to speak its language, to feel its rhythm, and to be moved by its complex simplicity. It’s a journey through sound that promises new discoveries at every turn, for those willing to listen deeply.

The Global Echo of Bebop

The Global Echo of Bebop reverberated far beyond its American birthplace, resonating across continents and cultures, proving that this was not just a musical style but a universal language.

Bebop Across the World: International Reception witnessed an enthusiastic embrace from afar. From the smoky cafes of Paris to the underground clubs of Tokyo, Bebop found a home among those hungry for its innovative spirit. It was a sound that crossed borders with ease, infusing itself into the fabric of various musical traditions and becoming a beacon of modernity and sophistication. In countries like France, where jazz had long been revered, Bebop was greeted as the next chapter in the evolving narrative of jazz, celebrated in festivals and concert halls from Lyon to Nice.

The Evolution of Bebop in Europe was a vibrant tapestry of adaptation and integration. European musicians, imbued with their own rich musical heritages, seized Bebop’s complexity and spun it with new threads. In cities like Copenhagen and Stockholm, a new strain of Bebop began to emerge—one that mingled with the continent’s classical traditions and produced a hybrid that was both fresh and familiar. Names like Django Reinhardt and later, the Swedish baritone saxophonist Lars Gullin, became synonymous with this European interpretation of Bebop, adding their unique accents to the Bebop dialect.

Bebop in Japan: A Cultural Fusion manifested itself in a profound way, as Japan embraced Bebop not only as a music form but as a cultural statement. In the post-war era, Bebop became a symbol of freedom and renewal, its fast-paced and unpredictable rhythms reflecting the rapid changes within Japanese society itself. Musicians like Toshiko Akiyoshi took Bebop and infused it with the essence of Japanese musicality, creating a fascinating cross-cultural dialogue. The Tokyo jazz scene became a hotbed of Bebop, with musicians there contributing to its global evolution and ensuring its place in the annals of jazz.

Through this global journey, Bebop became more than just a genre; it became a movement that transcended its origins. It was a conversation between cultures, each learning and borrowing from the other, each adding their voice to the chorus that Bebop had begun. This was not just an echo; it was a response, a worldwide affirmation that Bebop had indeed caused a revolution—a revolution that continues to resonate to this day.

The Controversies and Criticisms of Bebop

The Controversies and Criticisms of Bebop are as integral to its story as the notes themselves, revealing a genre that stirred as much debate as it did admiration.

The Pushback Against Bebop was immediate and, at times, fierce. Traditionalists saw it as a cacophony, a renegade sound that strayed too far from the harmonious melodies of jazz’s roots. The fast tempos and complex chord progressions were branded as musical anarchy by some critics, who lamented the loss of the danceable rhythms of swing. Bebop was revolutionary, and like all revolutions, it faced opposition from those who held dear the status quo.

Commercialism vs. Artistry: The Bebop Dilemma was a tug of war that tugged at the very soul of the genre. On one side, there were purists who considered Bebop to be the pinnacle of artistic expression, uncorrupted by commercial interests. On the other side were practical realities—venues and record labels that needed music that sold. The intricate and often introspective nature of Bebop was a hard sell to a public that craved the familiar. This schism led to a debate that questioned whether Bebop could maintain its artistic integrity while achieving commercial success.

The Debate: Bebop’s Place in Jazz History is an ongoing discourse among aficionados and critics alike. Was Bebop a fleeting moment, a blip on the radar of jazz history? Or was it a transformative force that redefined the boundaries of the genre? Detractors argue that Bebop’s influence was limited to a small circle of musicians and enthusiasts, while advocates see it as the foundation upon which modern jazz was built. This debate is not just about music; it’s about the very nature of innovation and tradition, of evolution versus preservation.

Bebop stands as a testament to the restless spirit of musical exploration. The controversies and criticisms are but a testament to its impact—a genre that did not merely suggest change but demanded it. Whether seen as a discordant noise or a symphonic revolution, Bebop’s place in the pantheon of jazz is indelibly inked, its legacy a rich subject of discussion for all who follow the call of this most adventurous music.

Preserving Bebop: The Modern Scene

Bebop in Education: Jazz Studies Programs have become sanctuaries of Bebop’s preservation, fostering new generations of jazz enthusiasts. Institutions like Berklee College of Music and the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz are not just teaching the scales and chords; they’re imparting the philosophy behind the notes. Here, in these hallowed halls of learning, students dissect Charlie Parker’s solos with the precision of surgeons and debate Dizzy Gillespie’s techniques with the passion of philosophers. These programs are less about creating carbon copies of Bebop greats and more about instilling the innovative spirit that birthed the movement.

Bebop Revival: The Contemporary Scene is where the vintage sound of Bebop meets the freshness of the new age. Artists like Kamasi Washington and Robert Glasper are fusing the core tenets of Bebop with contemporary elements from hip-hop, soul, and beyond, proving that Bebop is as malleable as it is timeless. Clubs around the world, from the Blue Note in New York to Ronnie Scott’s in London, are showcasing Bebop’s vibrancy, with musicians who play these classic tunes with a reverence that is palpable and a freshness that is invigorating.

The Digital Age: Bebop’s Online Presence has exploded, ensuring that this revolutionary genre remains accessible to all. Streaming services offer vast libraries of Bebop recordings, while social media platforms enable aficionados to share rare finds and discuss the minutiae of this intricate art form. Online forums buzz with discussions of Bud Powell’s intricate fingerings or Max Roach’s polyrhythmic prowess. Bebop’s essence is also captured in the digital ether through online masterclasses and virtual performances, bridging the gap between the old and the new.

In the modern scene, Bebop is not just being preserved; it’s being celebrated and reincarnated, its spirit as alive today as it was in the smoky clubs of 52nd Street. It continues to evolve, proving that while the riffs may belong to a bygone era, the revolution is ongoing. The notes of Bebop still leap from the pages of history, as fresh and as revolutionary as they were at their inception, ensuring that this groundbreaking genre continues to capture hearts and stimulate minds.

The Future of Bebop

The Future of Bebop stretches before us, as boundless and beguiling as the improvisations it champions. It’s a genre that refuses to be archived as a mere historical curiosity. With each new generation of musicians who discover its complex joys, bebop renews itself, defiantly proving it is not a relic but a living, breathing form of musical expression. The future sees bebop continuing to inspire, its principles applied to new sounds and technologies, ensuring its spirit of innovation is as infectious as ever.

Why Bebop Still Matters Today is a testament to its enduring vitality. Bebop remains a cornerstone of musical education, teaching not only technique but also the value of breaking rules and pushing boundaries. Its language, once avant-garde, now forms the essential vocabulary for any serious jazz musician, its influence resonating in the myriad of music genres that have followed in its wake. Bebop matters because it stands as a monument to creativity and artistic bravery, a beacon for those who dare to think differently.

Bebop, then, is more than a genre—it’s a philosophy, an attitude, and a challenge. It dares today’s musicians to innovate, to experiment, to play each note as if it could revolutionize the world. And it invites listeners to engage, to actively participate in the music, and to appreciate the sheer human genius that such artistry requires. As we look to the future, bebop’s place is secure—not just as a chapter in the history of jazz but as a continuing dialogue between past and present, artists and audience, tradition and the uncharted musical horizons that lie ahead.